It is always interesting to understand mathematical (or any) concepts when they are explained in simple intuitive ways.

– How long will it take to double your investment at a fixed compounding rate of 8%?

– What does the natural base e really mean (also known as Euler’s number)?

– What does it mean when they say slope of y = ex at any x is ex? (ok, this one in a separate future post but it highlights a fantastic fact about e!)

– what is exponential growth versus linear growth? (hopefully that is self evident at the end of this post)

Logarithms are an aid to understand and answer these types of questions!

Let’s start of with a simple equation: 24 = ?

The answer is of course, 16.

24 = 16

What does this actually mean in the context of “growing” ? It means if you start with 1 of something, and grow at the rate of 2 every iteration, then at the end of the 4th iteration you end up with 16 of that thing:

1 x 2 = 2

2 x 2 = 4

4 x 2 = 8

8 x 2 = 16

That’s four 2s above. I end up with 16 times what I started with. What if you tripled every iteration for 4 iterations? You end up with 81 times of that thing you started with:

34 = 3 x 3 x 3 x 3 = 81

In the above cases, the “growth rate” is 2 (double) or 3 (triple). If I wrote the above in logarithmic form, I end up with this:

log 2 16 = 4 (read as: “log 16 to the base 2 = 4”)

OR

log 3 81 = 4

Or in other words, if my growth rate is double each iteration, it takes me 4 iterations to reach 16 times what I started with. We are interested in the iterations in this example.

If I had $1 and I doubled it every iteration, I’d have $16 at the end of 4 iterations or 16 times what I started with (1 to 2 to 4 to 8 to 16 = 4 iterations)

Doubling it implies I grow at the rate of 100% every iteration. This may be true for bacteria or cells – 1 cell becomes 2, 2 becomes 4, 4 becomes 8 and so on. In the real world I wish my money doubled every iteration, but that would have to be some magical investment. Let’s say my money grows at a more realistic rate of 8% (instead of 100%) every year, or I earn 0.08 times the starting amount, every iteration. So then my growth rate is 1.08 every iteration. I had $1 initially, I have $1.08 at the end of an iteration.

At the end of the second iteration, I have $1.08 + (0.08×1.08) and so on. So plugging this growth rate into the logarithm form:

log1.08 X = y iterations?

What is X here though? Recall this below meant if I doubled every iteration and wanted to reach 16 times my starting amount I had to go through 4 iterations:

log2 16 = 4

In this example we want to double our investment so X is the multiple by which I want to grow which would be 2. So if I grow at 1.08 every iteration, how many iterations would it take for me to reach 2 times what I started with?

log 1.08 2 = y iterations

My logarithmic tables tell me the answer is: 9.006468342

I’ll approximate that number since that is good enough for this purpose: it would take me 9 iterations to get to a multiple of 2 if I grew by 8% every iteration. In the real world, that would normally mean 9 years (since the 8% is an annual compounded growth rate) to double my investment! (This is also called the rule of 72 which is if you divide 72 by the rate of return – 8% – you end up with the number of iterations to double your initial investment!)

No Growth

Continuing on with some more fun. What if you did not want to grow at all i.e. I want my growth multiple to be just 1? How many iterations would it take to not grow at all?

log1.08 1 = ?

The answer is 0. Of course! zero iterations! If you waited 0 years you would not have grown your investment at all. Which also brings up the interesting side story that anything raised to the zero index is 1:

1.08 0 = 1

In fact any growth rate raised to the 0 index would end up leaving you with exactly 1 unit of what you started with!

Fractional Growth

What would a fractional growth rate give you?

log 0.5 2 = ?

What does this even mean? It means I’m shrinking by 50% every iteration! When would I have double my starting number if I shrank by 50%? It does seem like an absurd question but the answer tells you something interesting:

log 0.5 2 = -1

A negative 1? Yes! What it is essentially telling you is you’d have to go an iteration in the past if you wanted to see your investment double! Fair enough – we are shrinking by half every iteration as we move into the future. Or in other words:

0.5-1 = 2

Your traditional definition of “x raised to the power of y means repeated multiplication of x, y times” may not seem intuitive enough to solve the above problem! It is tricky to explain what raising to a negative power means unless there is a context of growth and time involved in the explanation. Also where can negative growth make sense? If you’ve heard of “radio-carbon dating” to estimate ages of prehistoric organic material it may start to make sense!

EULER’S NUMBER

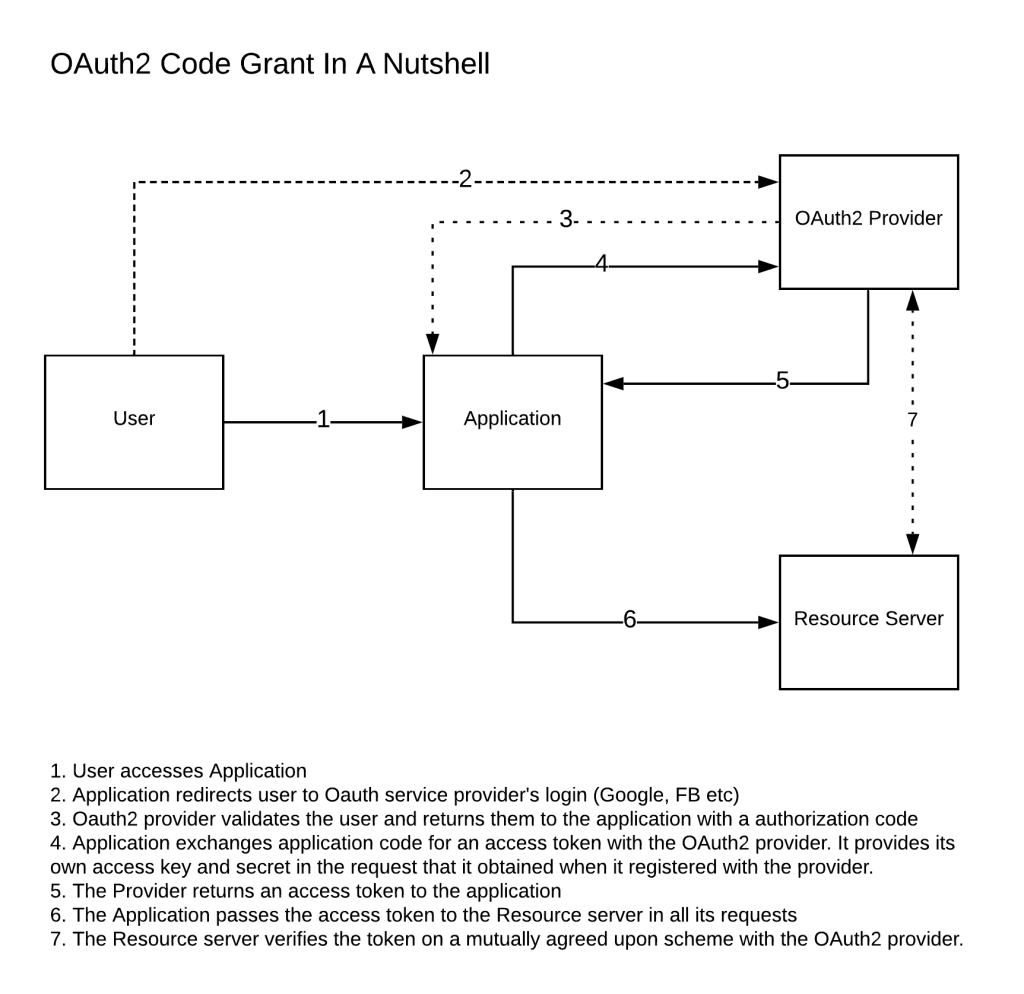

So what is Euler’s number or e? This famous number is something found in nature wherever compounding growth is involved: money, rabbits, cells, population etc. In the compound interest solution that we saw earlier where the growth rate was 1.08 we saw that things doubled after about 9 intervals or iterations. What if we increased the iterations and divided the growth rate evenly by those same number of iterations? In other words given this:

(1 + .08/1)1 = the growth after one iteration

(Note that the .08 growth is over 1 time period so we have the “.08/1” in the equation and since we are looking at what we have at the end of 1 interval it is raised to the power of 1). What if the bank compounded the rate twice in a year? Or:

(1 + .08/2)2

For simplicity lets assume the growth rate is 100% i.e. 1 not 0.08. So:

(1 + 1/2)2

| frequency of compounding | growth multiple | |

| (1 + 1/1)1 | 2 | compounded 1 times |

| (1 + 1/2)2 | 2.25 | compounded 2 times |

| (1 + 1/12)12 | 2.61303529022 | compounded monthly |

| (1 + 1/365)365 | 2.71456748202 | compounded daily |

| (1 + 1/1000)1000 | 2.71692393224 | compounded a 1000 times |

| (1 + 1/10000)10000 | 2.71814592682 | compounded 10,000 times |

Well, you can see a pattern above – the growth multiple jumps up by large increments (2, 2.25, 2.61..) but as we tend to increase the number of compounding intervals the final value approaches a magical number that begins with 2.7. No matter how many times you compound (“..to infinity and beyond!”) you will only make very minor increments but never go past the 2.7xxxx boundary. This is Euler’s number or e. No matter how many times you compound your starting amount you cannot end up with more than e‘s multiple of what you started with. Also, e is an irrational number who’s end is not known just like PI.